The Big Fella: Michael Collins and the Irish Independence Movement

Posted by Pete on 22nd Aug 2021

Killed on this day in 1922, Michael Collins was a revolutionary like no other

In its overlong history, the British Empire was challenged by many rebels from all over the world. But none of them was quite like Michael Collins (1890-1922).

A farmer’s son from County Cork, Collins grew up to be the most famous commander in the Irish independence struggle.

Cork was rebel country, so Collins lived and breathed Irish republicanism from a very young age.

He worked in London and New York as a young man, and diaspora life only fuelled his commitment to Irish independence. It was in London that he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

Collins then came back to Ireland to work as an accountant in Dublin, just in time for the Easter Rising of 1916…

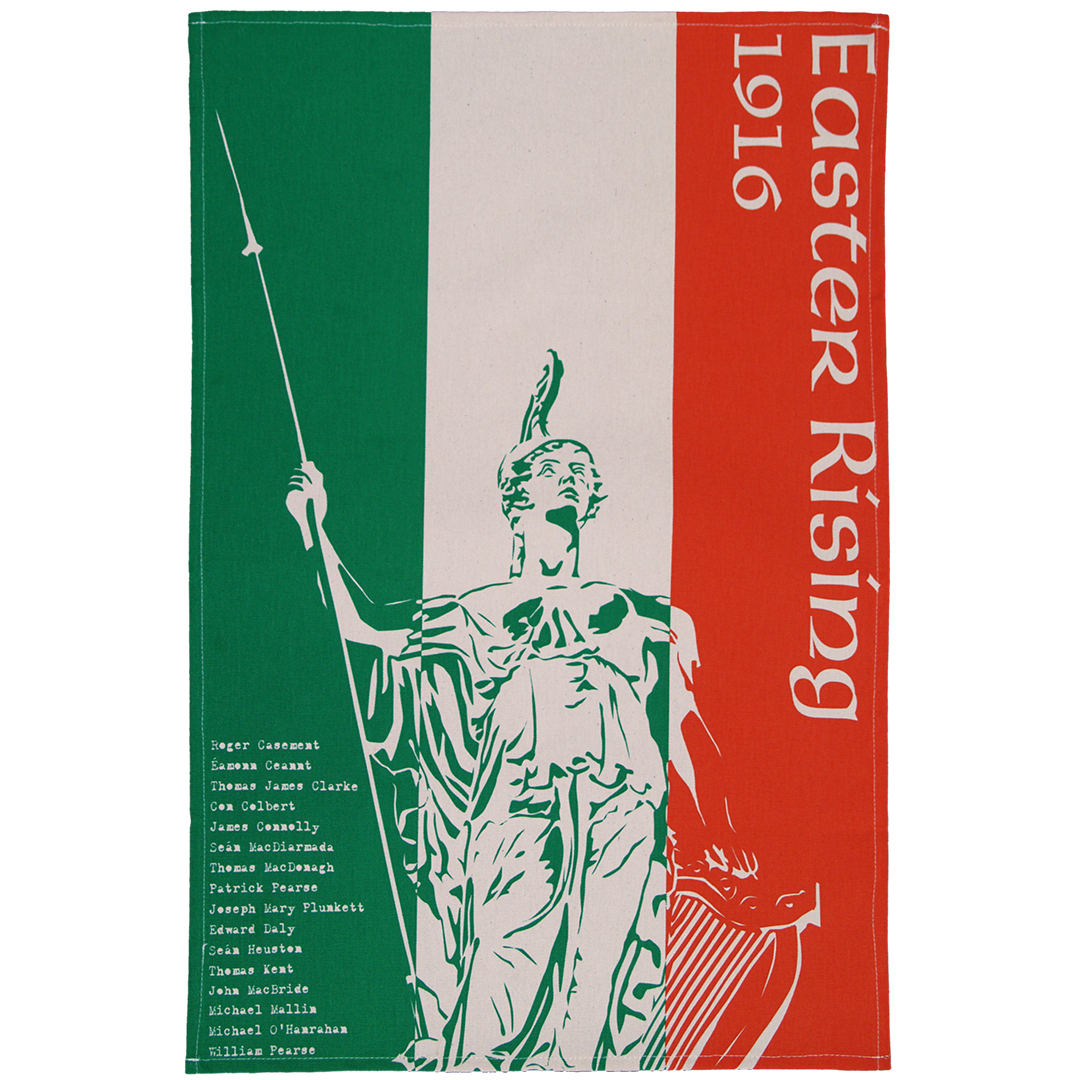

The Easter Rising of 1916 was the first armed conflict of the Irish revolutionary period of the 1910s and 20s.

Click to view our Easter Rising tea towel

Alongside the older generation of Irish nationalists, figures like James Connolly and Constance Markievicz, he fought until he was captured by the British Army.

Narrowly avoiding execution alongside the senior leadership in Dublin, Collins was sent to Frongoch prison in Wales.

Self-defeating as always, the British government turned its own prison system into an organisational structure for the Irish republicans.

Concentrated in the same few prisons, the Irish were able to build new links and plan the next phase of the independence struggle.

Collins emerged from these months with a newfound seniority in the movement, especially now that the old leadership had been mostly executed by the British.

Released at the end of 1916 after widespread demands for an amnesty, Collins didn’t falter: campaigning for independence resumed immediately.

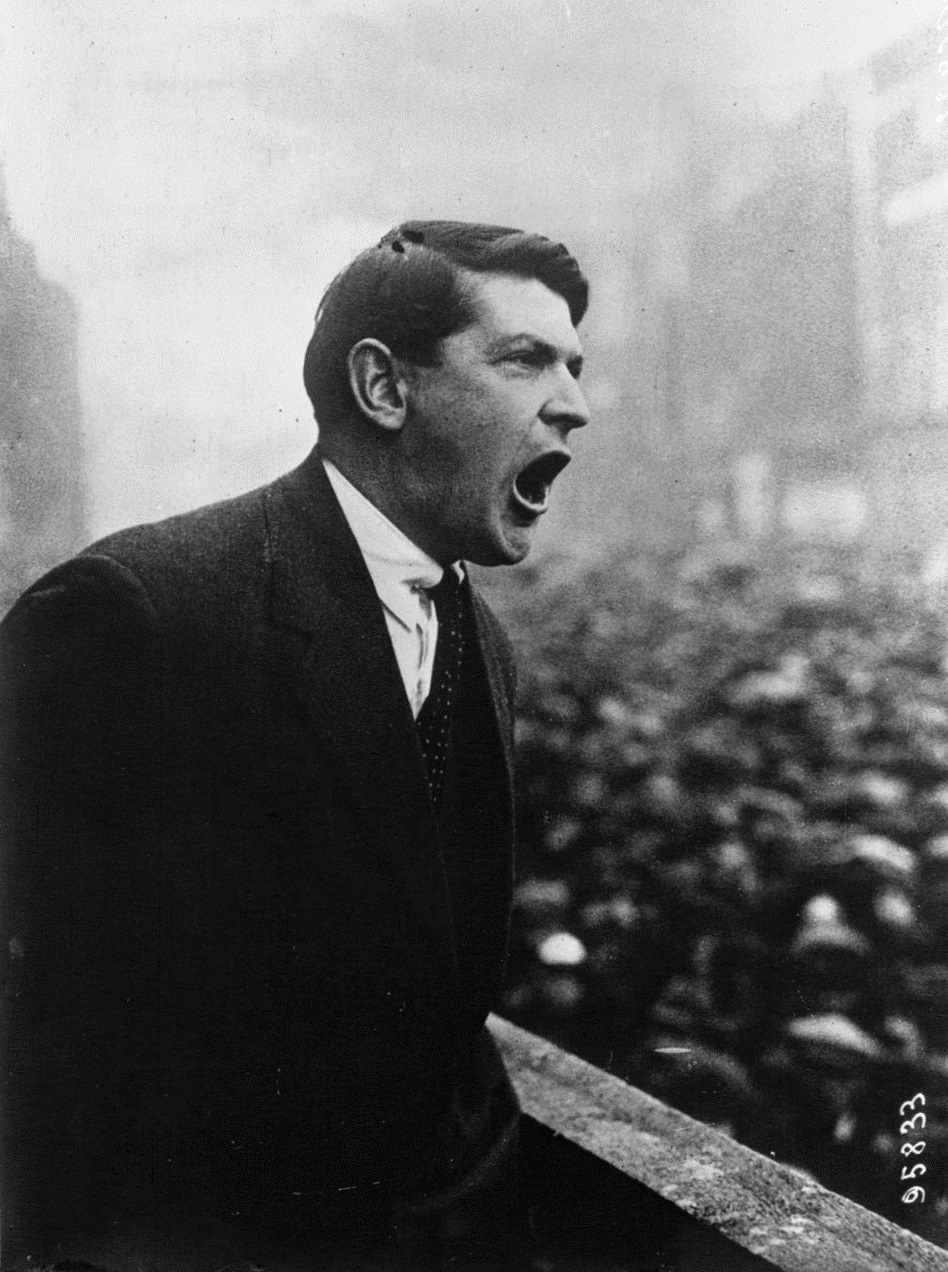

Michael Collins passionately working the crowd in Dublin in 1922.

Sinn Féin won the 1918 General Election in Ireland with a landslide, decimating the old Irish Parliamentary Party which had sought Home Rule without independence.

True to its word, Sinn Féin MPs did not go to Westminster – the Party rejected its authority in Ireland. Instead they created their own parliament in Dublin, the Dáil Éireann, which opened in January 1919.

By this point, a military conflict for independence was becoming inevitable.

David Lloyd-George’s coalition government of Liberals and Tories had already ordered the arrest of most Sinn Féin leadership.

At the beginning of 1919, full-scale armed conflict broke out between British forces and the Irish Republican Army, which the Dáil adopted as the armed force of the new Irish Republic.

Bold, smart, and strategic, Collins took effective command of the Irish military and espionage efforts during the War of Independence.

His task was all but impossible.

Like Michael Collins, Constance Markievicz was among the 73 Sinn Féin MPs elected in the 1918 General Election and who went on to form the first Dáil Éireann.

Click to view our Constance Markievicz tea towel

Lloyd-George and Winston Churchill were intent on savage violence to keep Ireland in the British Empire.

Brutal paramilitary units like the ‘Black and Tans’ were created and sent to Ireland, where they assaulted and murdered POWs and civilians with impunity.

But under Michael Collins’ command, the IRA held out long enough for Lloyd-George to request peace talks.

The terms on offer were dire, with the British ruling out an Irish Republic and insisting the North of Ireland, with its cluster of Unionists, be kept in the UK.

But Collins, who was made to lead the Irish delegation in London, got the best terms possible – much of which the British soon reneged on.

He said the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 gave Ireland

“…not the ultimate freedom that all nations desire and develop to, but the freedom to achieve it.”

Regardless, the Treaty cut a deep division into the Irish nationalist movement.

An Anti-Treaty coalition led by Éamon De Valera refused to accept it.

And it wasn’t long before Civil War broke out, with Collins reluctantly leading the pro-Treaty ‘Provisional Government’ against his old comrades.

Backed by the British (an absurd and unwanted situation for Collins), the Provisional Government was soon on top.

Then, 99 years ago today, Michael Collins was assassinated by anti-Treaty forces.

He had been visiting his home county of Cork, hoping to agree peace with the republicans there and bring the war to a close.

Mourned by 500,000 people in Dublin, it was a tragic end for the ‘big fella’, as they used to call him. Slain by his old comrades while fighting alongside a British government he despised.

But the ultimate defeat belonged to Lloyd-George and the British Empire.

Michael Collins had helped to dislodge the first brick of the imperial wall. Within decades, all the others – India, Ghana, Myanmar, Jamaica, and so many more – would come tumbling down.

Key years in Michael Collins's life

- 16 October 1890: Michael Collins born in Woodfield, County Cork

- 1906: Collins moves to London to work as a clerk in the Post Office Savings Bank

- 1915: Collins briefly moves to New York

- 1916: Collins returns to Dublin

- 24-29 April 1916: Easter Rising – Collins participates as an Irish Volunteer and is captured

- December 1916: Collins released from prison

- December 1918: Sinn Féin win an electoral landslide in Ireland

- January 1919: Dáil Eireann opens and the Irish War of Independence begins, with Collins commanding republican forces

- July 1921: Ceasefire

- 6 December 1921: Anglo-Irish Treaty, negotiated and signed by Collins

- June 1922: Irish Civil War breaks out between Anti-Treaty Republicans and Pro-Treaty forces led by Collins

- 22 August 1922: Michael Collins is assassinated in Béal na Bláth, County Cork, aged 31