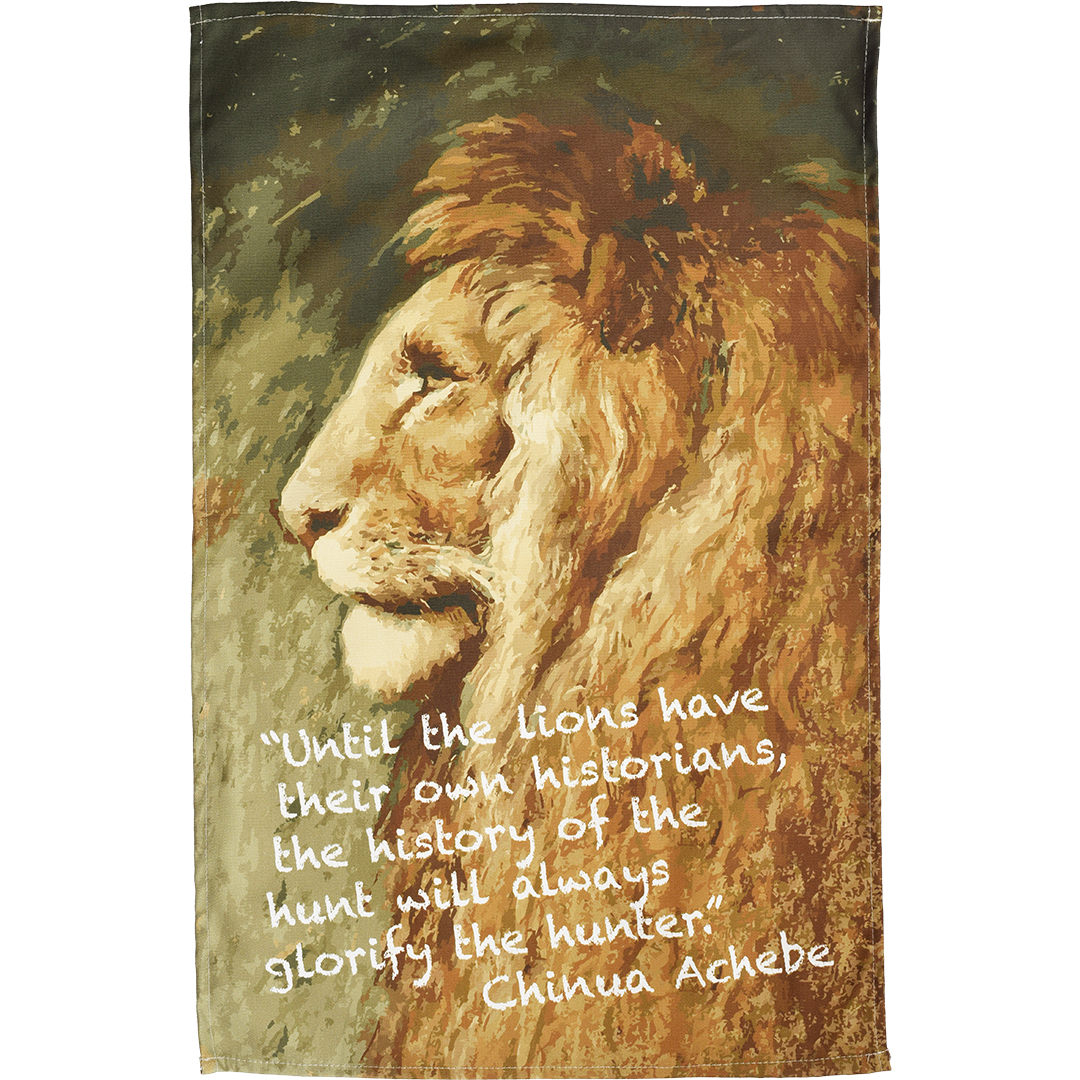

Chinua Achebe: The Lion's Historian

Posted by Pete on 22nd Nov 2022

The life and work of one of Africa's most celebrated writers...

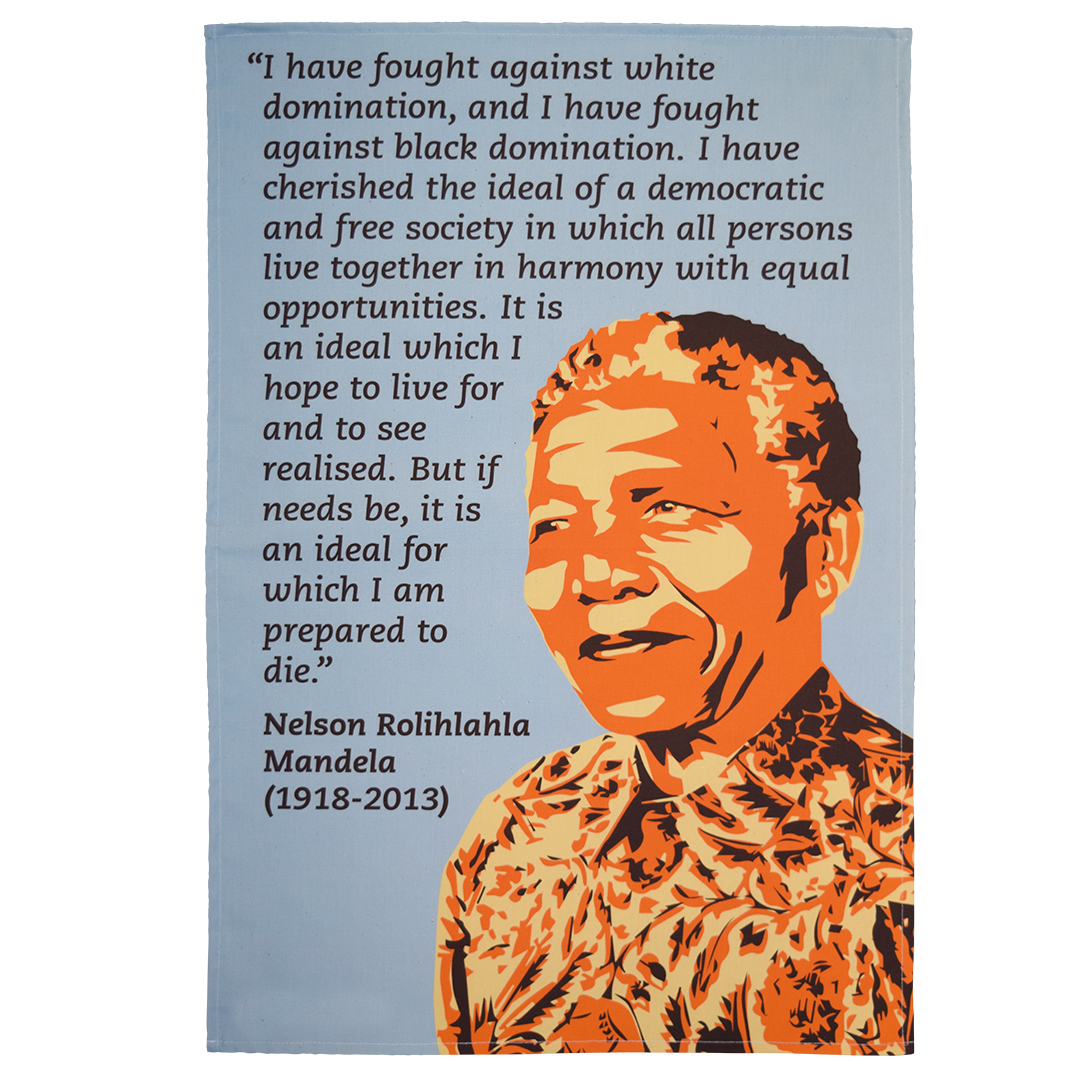

“There was a writer named Chinua Achebe… in whose company the prison walls fell down.”

Nelson Mandela

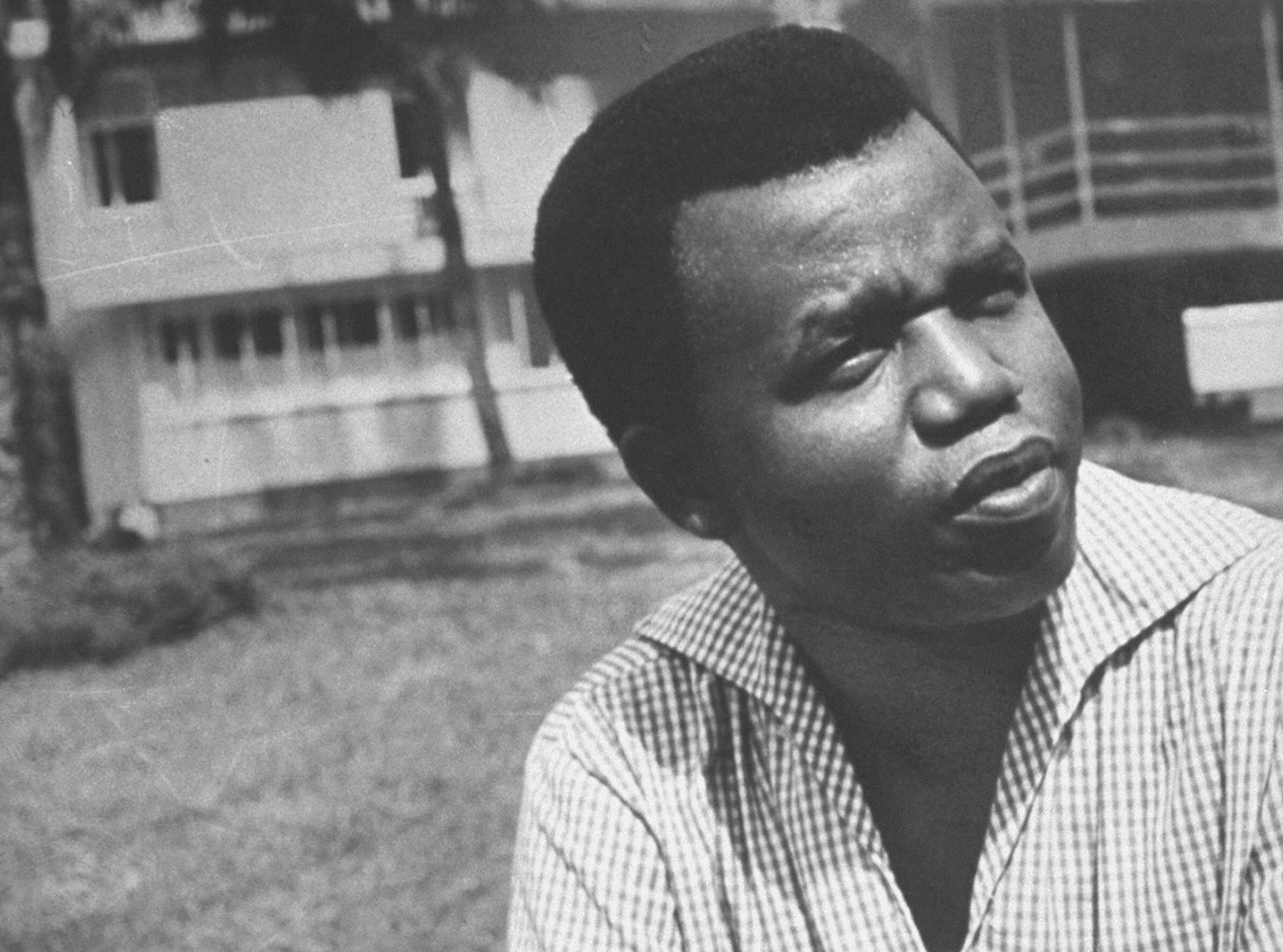

Chinua Achebe was born on the 16th November, 1930.

He came from Ogidi, in southeast Nigeria, at a time when the country was breaking away from British colonial rule – Nigeria became independent in 1960.

Achebe grew up in a time of significant change in his country, when the traditions of the Igbo people were being gradually supplanted by Protestant Christianity.

He was an academic star at school, gaining a scholarship to study medicine at the new University of Ibadan in 1948.

But Achebe had a different destiny in store for him.

Our new Chinua Achebe tea towel is out now on our website, featuring an image based on Géza Vastagh's Study of a Lion

Click to view our Chinua Achebe tea towel

During his medical degree, Achebe read as much of the European literary canon as he could.

He loved fiction, but he found that the famous Western depictions of Africa, like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, were all absurd and offensive to the actual people there.

In response, Achebe decided to become a writer, not a doctor. He meant to heal Africa and its peoples from the wounds these Western authors had inflicted on them.

Achebe’s first book, Things Fall Apart, was published in 1958 by Heinemann publishers in London.

He explored the tensions and violence involved in the clash of Igbo ways of life and British colonisation.

Despite the discouragement and condescension of many in the English publishing world, Things Fall Apart was a huge success.

And this was only the start.

Nelson Mandela was a huge fan of Achebe, whose work he said "brought Africa to the rest of the world"

Click to view our Nelson Mandela tea towel

Things Fall Apart would be the first of several books across fifty years of writing fiction, political thought, and poetry.

It also raised Achebe’s status inside Nigeria, where he became a major public intellectual.

Achebe got to tour Africa, Europe and North America on academic scholarships. In 1961, he met Arthur Miller in the U.S.

But Achebe’s life was also full of politics. The ills of colonialism and racism which he depicted and diagnosed in his novels were everywhere around him in post-WW2 Africa.

In 1960, while touring the white-ruled apartheid state of Northern Rhodesia – now Zambia – Achebe sat in the whites-only section of a bus to Victoria Falls.

When confronted by the steward about why he, a black man, was sitting there, Achebe answered:

“if you must know, I come from Nigeria, and there we sit where we like on the bus.”

But things were increasingly uneasy back in Nigeria, too.

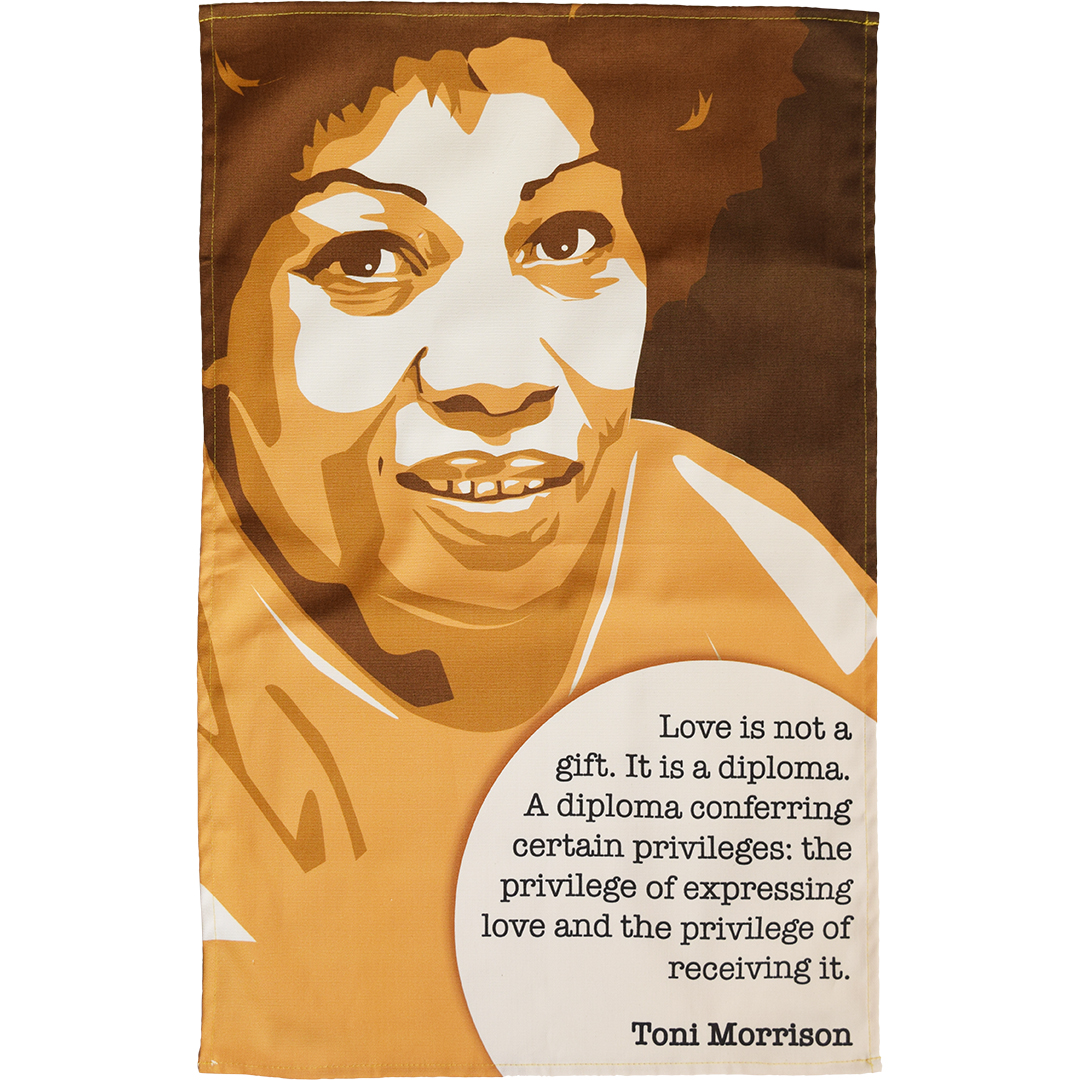

Nobel laureate Toni Morrison said that reading Achebe's work was what first inspired her to become a writer

Click to view our Toni Morrison tea towel

Postcolonial Nigeria had some deep divisions, between regions, classes, and cultures. Most of these had been actively cultivated or invented by the British Empire in order to divide-and-rule.

In May 1967, Achebe’s mostly-Igbo home region of Biafra, in the southeast of Nigeria, declared itself independent.

The Republic of Biafra fought on the principle of national self-determination, and Achebe rallied to its cause.

He lived under heavy bombardment in several Biafran cities, and served the country as an international ambassador in Europe and North America.

But geopolitics were stacked against the new state. Despite the ongoing Cold War, both Britain and the U.S.S.R. supported the Nigerian federal government, showering it with guns to crush Biafra, even as the region fell into a horrific famine due to the war.

Biafra surrendered in January 1970, and was reincorporated into Nigeria.

Achebe was disheartened politically, but returned to focus on his academic work.

In 1975, with a professorship at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Achebe delivered a famous critique of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as a racist text:

“It’s not in my nature to talk about banning books. I am saying, read it – with the kind of understanding and with the knowledge I talk about. And read it beside African works.”

After retirement in 1976, Achebe carried on writing for several decades. He continued his exploration of Igbo culture, modernity, colonialism, corruption, and more beside.

A giant of modern literature, influencing the likes of Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou, Chinua Achebe died in 2013.

He had spent a lifetime struggling against the intellectual denigration of his continent. As Achebe would say:

“If you don’t like someone’s story, write your own.”