Gregor MacGregor: The most absurd radical of the 19th century

Posted by Pete on 24th Dec 2024

Born on Christmas Eve, he was one of the most bizarre radicals of the 19th century

The radical past contains a range of characters.

Mixed in with the legions of principled and disciplined activists, there’s also been the occasional chancer or huckster...

And there’ve been few hucksters in radical history more absurd than Gregor MacGregor.

Gregor MacGregor, depicted as a revolutionary fighter in the early 19th century

Born on Christmas Eve 1786 in Stirlingshire, Scotland, MacGregor is best-known as one of the most audacious confidence tricksters ever.

Between 1821 and 1837, he defrauded thousands of investors in Britain and France by promoting a settlement scheme in a place called Poyais in Central America, despite the fact that ‘Poyais’ was completely made-up.

But before 1821, MacGregor had made his name fighting in the Latin American liberation army of Simón Bolívar.

MacGregor’s time in the independence struggle was hardly untainted.

But he did still take some genuinely heroic actions during the time of the Spanish empire in South America.

Remembered as a pioneer of modern financial fraud in Europe, in South America MacGregor was loved as a revolutionary during his time.

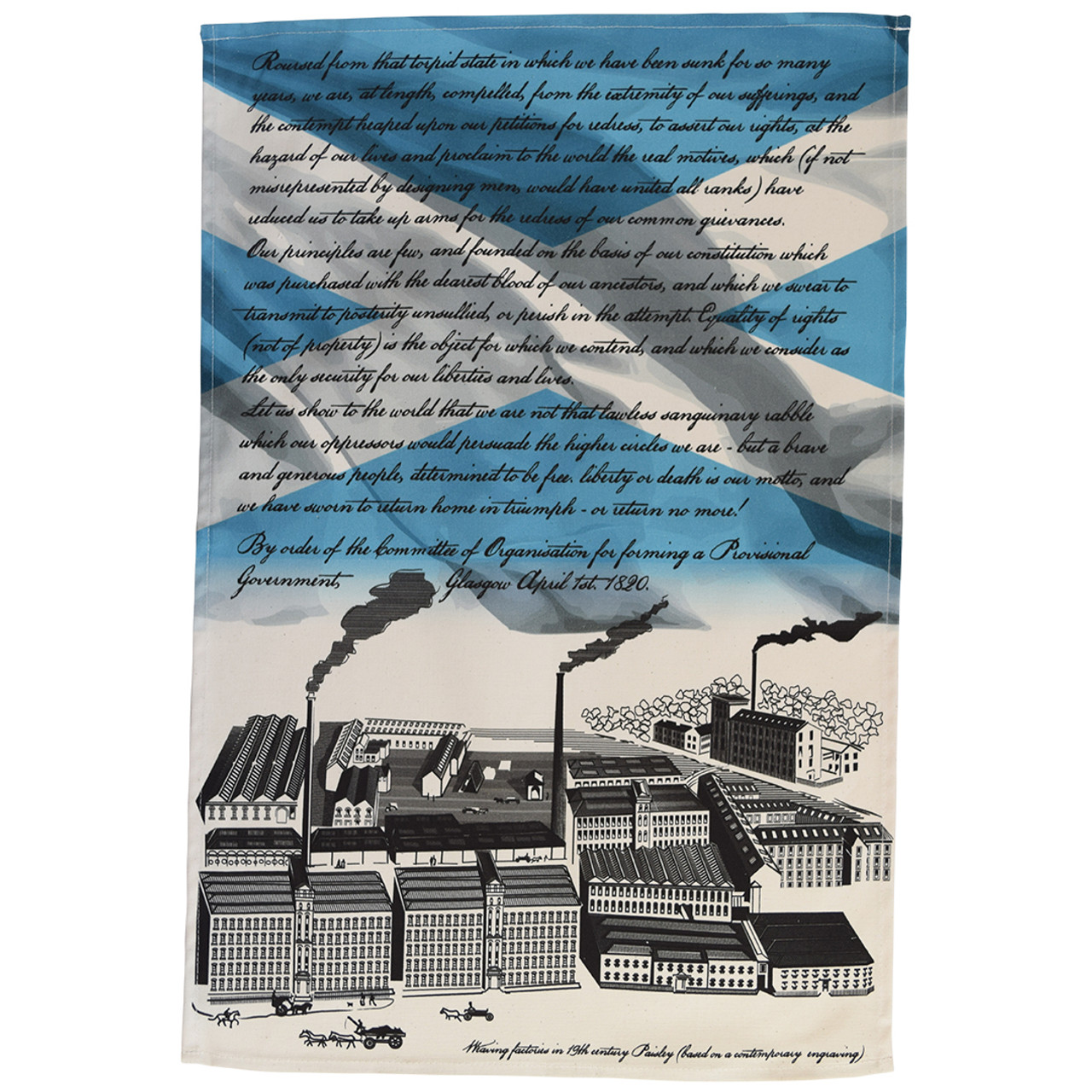

Birthplace of Gregor MacGregor, Scotland was a regular source of radicals and radical activity in the early 19th century

See the Scottish Radical War tea towel

Gregor MacGregor was born into the Scottish aristocracy.

His clan actually did have something of a radical past, having taken part in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745.

But by the time Gregor was born in 1786, the MacGregor clan had been rehabilitated thanks to his grandfather’s service in the British Army.

Gregor decided on a military career, too, joining the Army in 1803 when he was still just a teenager.

MacGregor served in Spain and Portugal during the Napoleonic Wars, after the French invasion of 1808.

He was already showing signs of his later vices, including an obsession with Georgian high society and its pretentious norms, and a willingness to lie about his military record whenever convenient.

MacGregor often claimed he’d fought at the Battle of Albuera in Spain in May 1811, which took place after he'd retired from the British Army and returned to England!

In 1812, MacGregor took on a new adventure: he volunteered to fight for the independence revolutions in Spanish South America.

As repeated during the Spanish Civil War of the 20th century, thousands of volunteers left Britain and Ireland to support the Latin American revolutionaries of the 19th century

See the Spanish Civil War tea towel

A distant forerunner of the International Brigades that supported the Spanish Republic against Franco during the 1930s, thousands of volunteers sailed from Britain and Ireland during the 1810s and 1820s to support the Latin American revolutionaries.

MacGregor arrived in the Republic of Venezuela in April 1812, where he used his military ‘credentials’ – real and embellished – to get commissioned as a colonel alongside local revolutionaries like Simón Bolívar.

The new Venezuelan republic was in trouble, though, facing a serious royalist counter revolution, and MacGregor was soon on the frontline.

He led a successful cavalry attack on the Spanish royalists, but the Venezuelans’ first attempt at a republic soon collapsed.

In July, MacGregor was evacuated from the country with his new wife, Bolívar’s cousin, Josefa.

But MacGregor remained committed to the independence movements in the Spanish Caribbean.

He travelled to the port city of Cartagena de Indias, in modern-day Colombia, where he took part in defending the town against a brutal royalist siege.

In 1816, MacGregor rejoined the independence struggle in neighbouring Venezuela, where republicans had rebuilt since their defeat in 1812.

This spell included one of MacGregor’s few unambiguously impressive achievements as a revolutionary: he led a successful retreat across most of Venezuela, holding off repeated Spanish attacks on the republican rearguard and personally fighting on the frontline.

But it was pretty much all downhill from there.

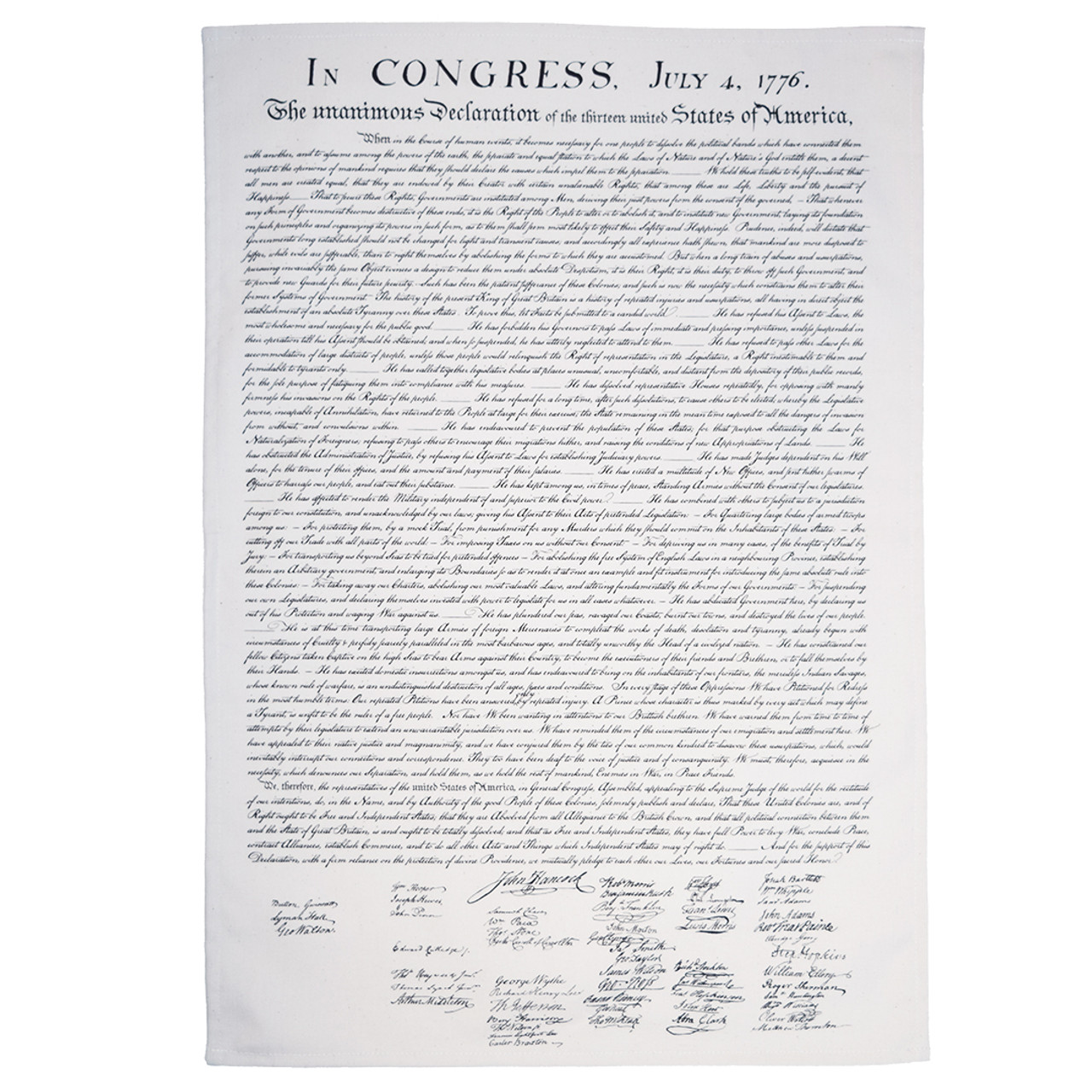

The South American revolutionaries sought to emulate the success of the colonists in North America in winning freedom from their European masters

See the Declaration of Independence tea towel

As Bolívar gained ground in Venezuela and Colombia, MacGregor took to the Caribbean Sea as a privateer for the independence movement.

MacGregor oversaw amphibious raids on Spanish positions in Florida and along the Colombian coast, but his actions were increasingly defined by self-interest and cowardice.

On several occasions, MacGregor abandoned his troops to save himself from Spanish counterattacks, and he repeatedly failed to pay them.

Bolívar eventually caught wind of the fact that MacGregor had become a charlatan, and he sentenced the Scotsman to death as a traitor.

Cut off from revolutionary Latin America, it was in this moment that MacGregor pivoted to launch his ‘Poyais scheme’ in Central America, defrauding faraway investors in London and Paris for personal enrichment.

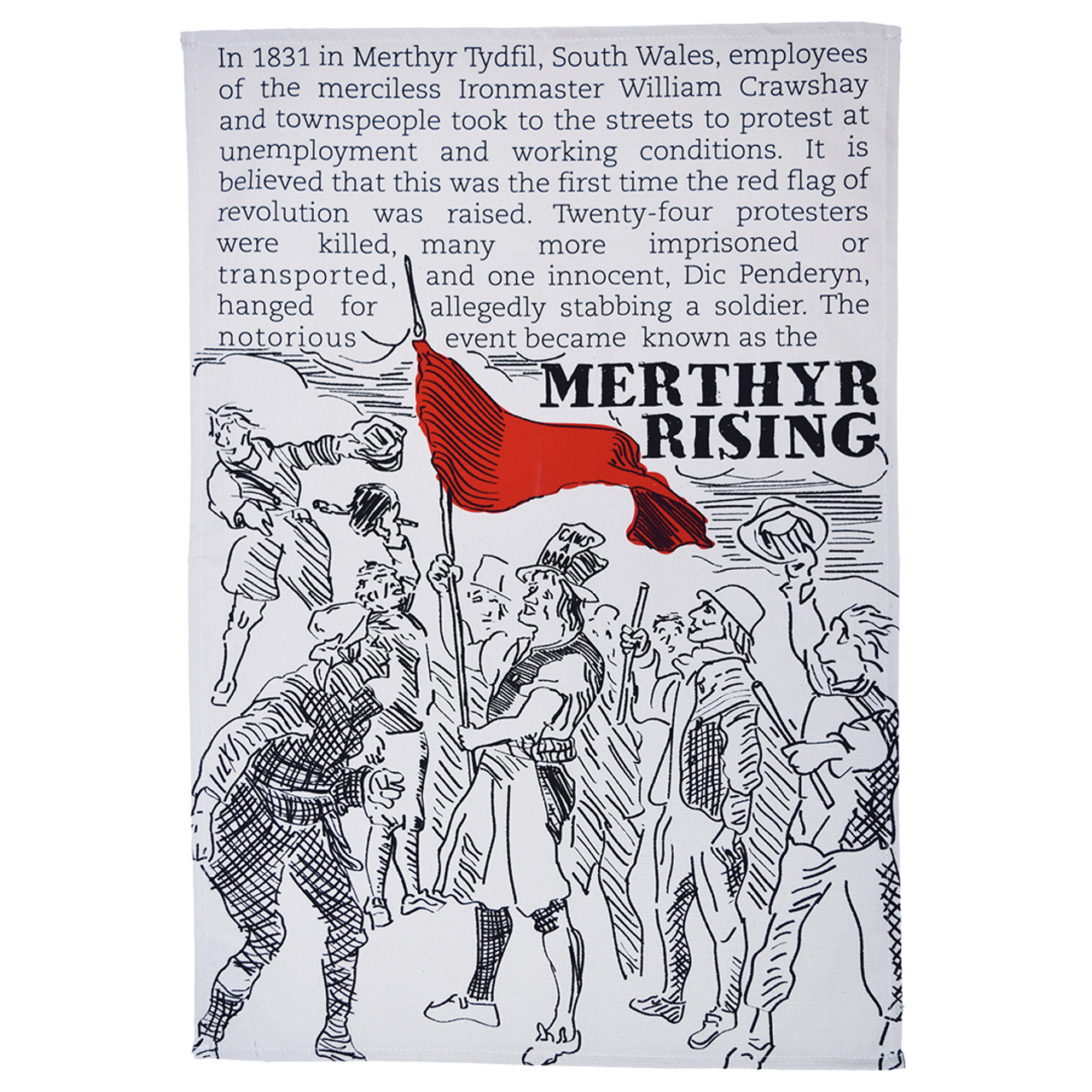

The early 19th century was a time of unrest in both the new world and old, with rebellions like the Merthyr Rising of the 1830s striking fear into the established authorities

See the Merthyr Rising tea towel

Despite his blatant character flaws, MacGregor was actually welcomed back to independent Venezuela in 1838, where he was lauded as a revolutionary ‘founding father.’

MacGregor spent his last years in Caracas, where he died in 1845, and was given a state funeral.

Gregor MacGregor – soldier, revolutionary, fraudster – is strange evidence of the fact that freedom struggles have, very occasionally, been able to make use of charlatans.

But they do well not to make a habit of it!