The National Hunger March: Before Jarrow, Glasgow

Posted by Pete on 26th Sep 2024

The traditional labour movement may not have realised the transformative potential of the unemployed masses of the 1930s, but the British state was well aware of the risk

NUUW march in London, 1930s. Used with kind permission from TUC Library

Four years before the Jarrow Crusade, the lesser known National Hunger March set out from Glasgow to London.

The Great Depression was destroying working-class life across Britain during the early 1930s, driving up joblessness and poverty, weakening communities and killing people.

Meanwhile, a vicious, right-wing ‘National Government,’ led by the Labour Party turncoat, Ramsay MacDonald, responded with austerity and police repression.

For unemployed workers – 2.75 million of them by September 1932 – even the trade union movement was no help.

The traditional, ‘moderate’ unions were still focused on their employed, dues-paying members, and the unemployed were notoriously difficult to organise, anyway.

But the Left in Britain wasn’t put off by the challenge.

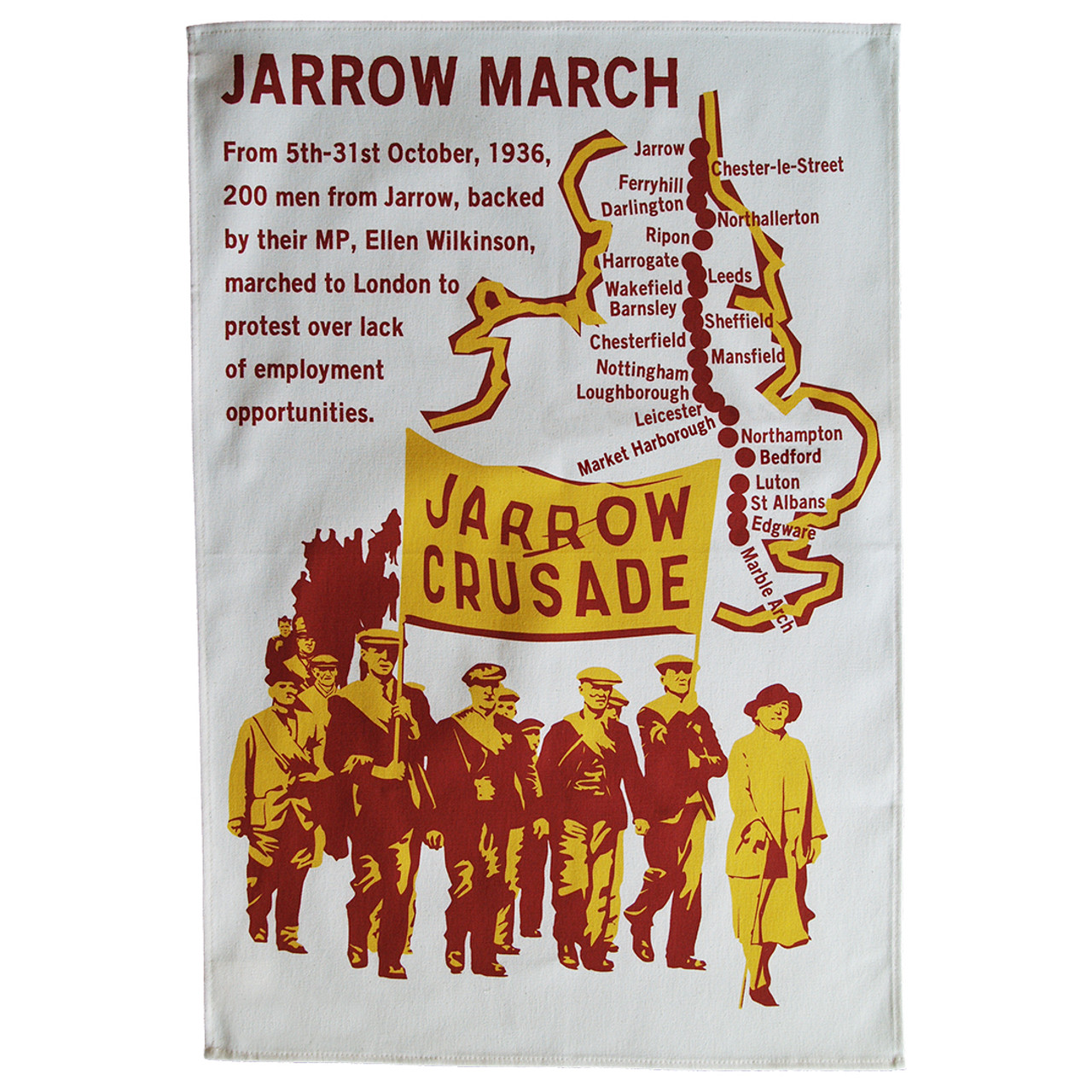

The Jarrow March of 1936, inspired by the earlier National Hunger March, became one of the defining moments of the decade

See the Jarrow March tea towel

Way back in 1921, some British communists had created the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM), and this organisation came to life in the context of the Depression.

While the mainstream labour movement continued to ignore the rising number of laid-off workers after 1929, the NUWM began to ready this group for political action.

On this day in 1932, the NUWM organised the Great National Hunger March.

3,000 unemployed workers would set out from all over the country, marching to London to protest the means test which the MacDonald government had chosen to introduce in order to cut state benefits and impose more poverty on the working class.

The first contingent of the march set out from Glasgow, a working-class citadel which had been especially wrecked by the Depression and the government’s handling of it.

Other groups started from similarly industrial areas with traditions of worker radicalism, like the South Wales coalfield and the North of England.

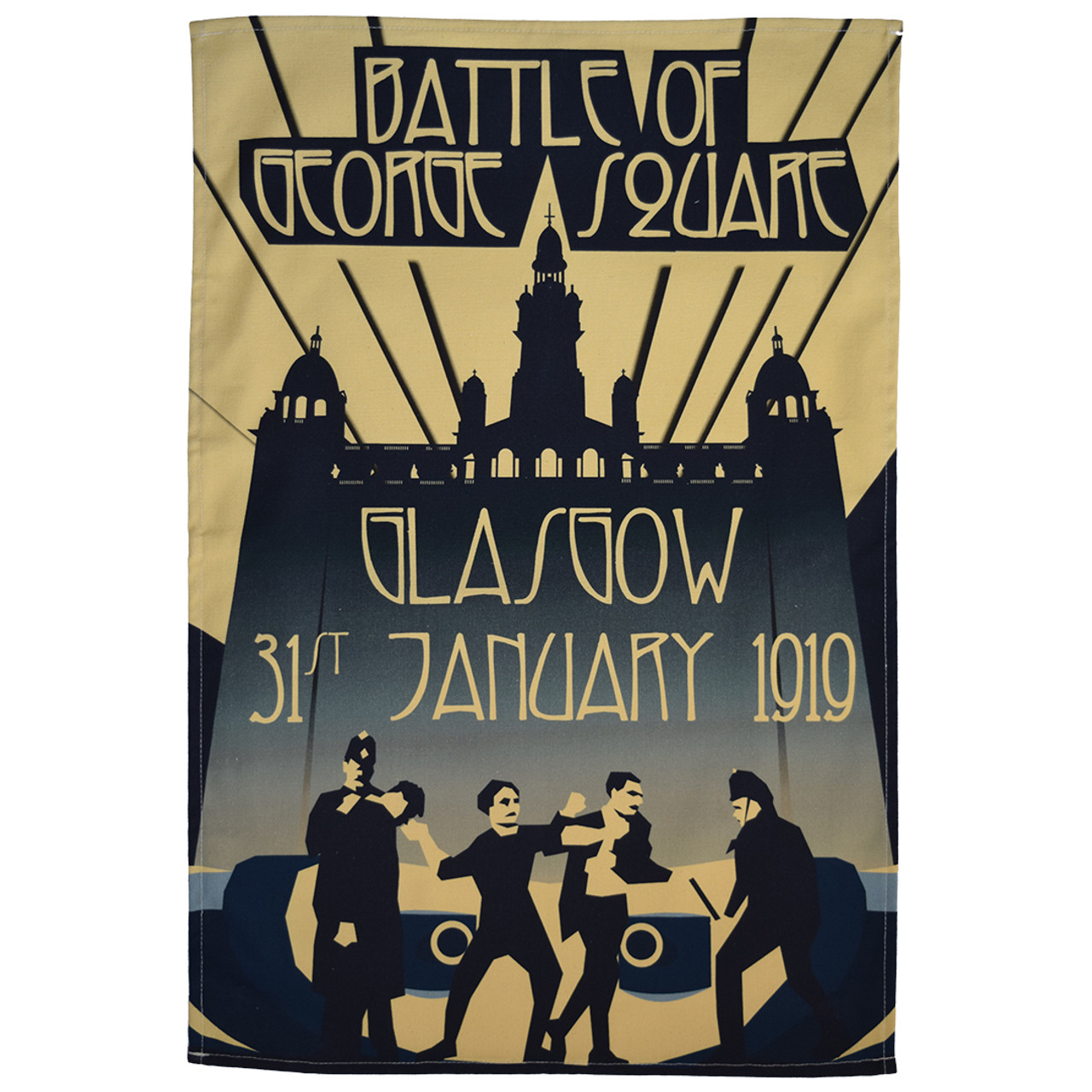

Glasgow had seen labour conflict well before the 1930s, including the Battle of George Square in the aftermath of WW1

See the Battle of George Square tea towel

Although themselves small in number, when the 3,000 hunger marchers reached London on 27 October, they were greeted by a crowd of 100,000 people who came out for a solidarity rally in Hyde Park.

But the march was also greeted by no fewer than 70,000 police – the largest police mobilisation by the British government since it feared a Chartist revolution in 1848.

That’s because, whereas the traditional labour movement didn’t realise the socially transformative potential of the unemployed masses, the British state did.

Capitalism in Britain was no longer able to provide even the basic means of survival for millions of workers, which turned these workers into a possible base for social revolution.

Rather than even try to ameliorate the economic roots of this political problem with an investment and welfare program like the New Deal in the U.S., MacDonald’s reactionary government decided to embrace brute violence, instead.

The NUWM marchers had brought with them a petition of 1 million signatures, but they were violently stopped from delivering it to Parliament by the police.

At Hyde Park, too, police charged down the unarmed assembly on horseback, and 75 people were severely injured across London in the course of the day.

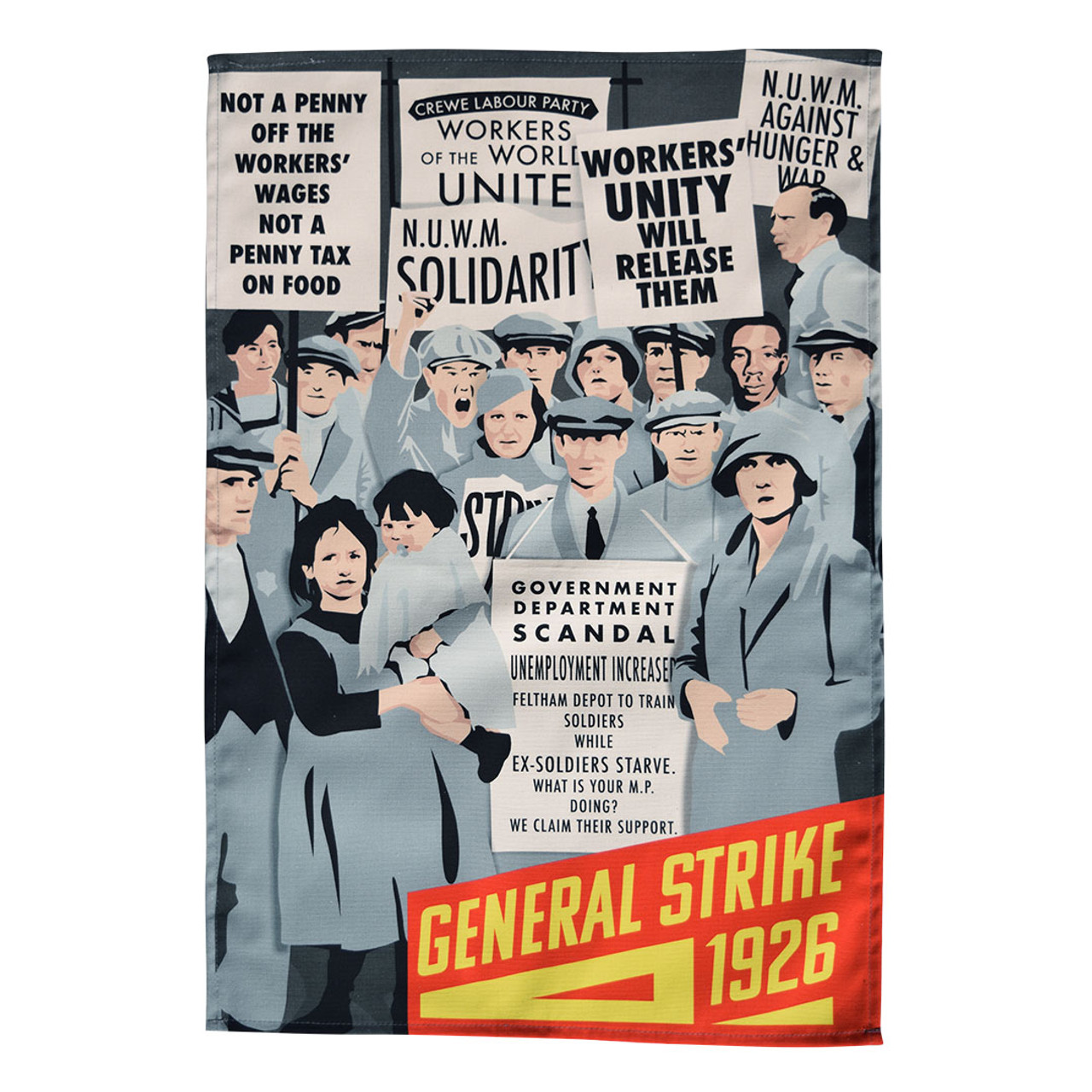

The 1920s and 1930s were a time of economic depression and acute conflict between British workers, employers and state, with events which have lasted in popular memory such as the 1926 General Strike

See the General Strike tea towel

As at Peterloo, the Battle of Trafalgar Square, and the General Strike of 1926, working-class politics in Britain was again met with no compromise, no democracy, and no quarter by the state.

But the National Hunger March, nonetheless, showed the remarkable staying power of worker radicalism in Britain even in the face of depression, impoverishment, and reaction.

Just four years later, the unemployed were marching again, in the Jarrow Crusade, and they'd keep going until the struggle for working-class survival, dignity, and liberation was won.