The Women Trade Unionists

Posted by Pete on 6th Nov 2024

This week in 1919, the International Congress of Women Workers took place in Washington DC

The National Federation of Women Workers (NFWW), established in 1906, was the first ever nationwide trade union for women in Britain.

Most unions in Britain refused to allow women members during the nineteenth century, and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) only agreed to admit them as members of women-only unions.

In part, this was down to working-class men reproducing the puritanical, sexist social norms of the elite in Victorian Britain. Norms that were hostile to the presence of women in public life, including the labour market, and especially in gender-mixed settings.

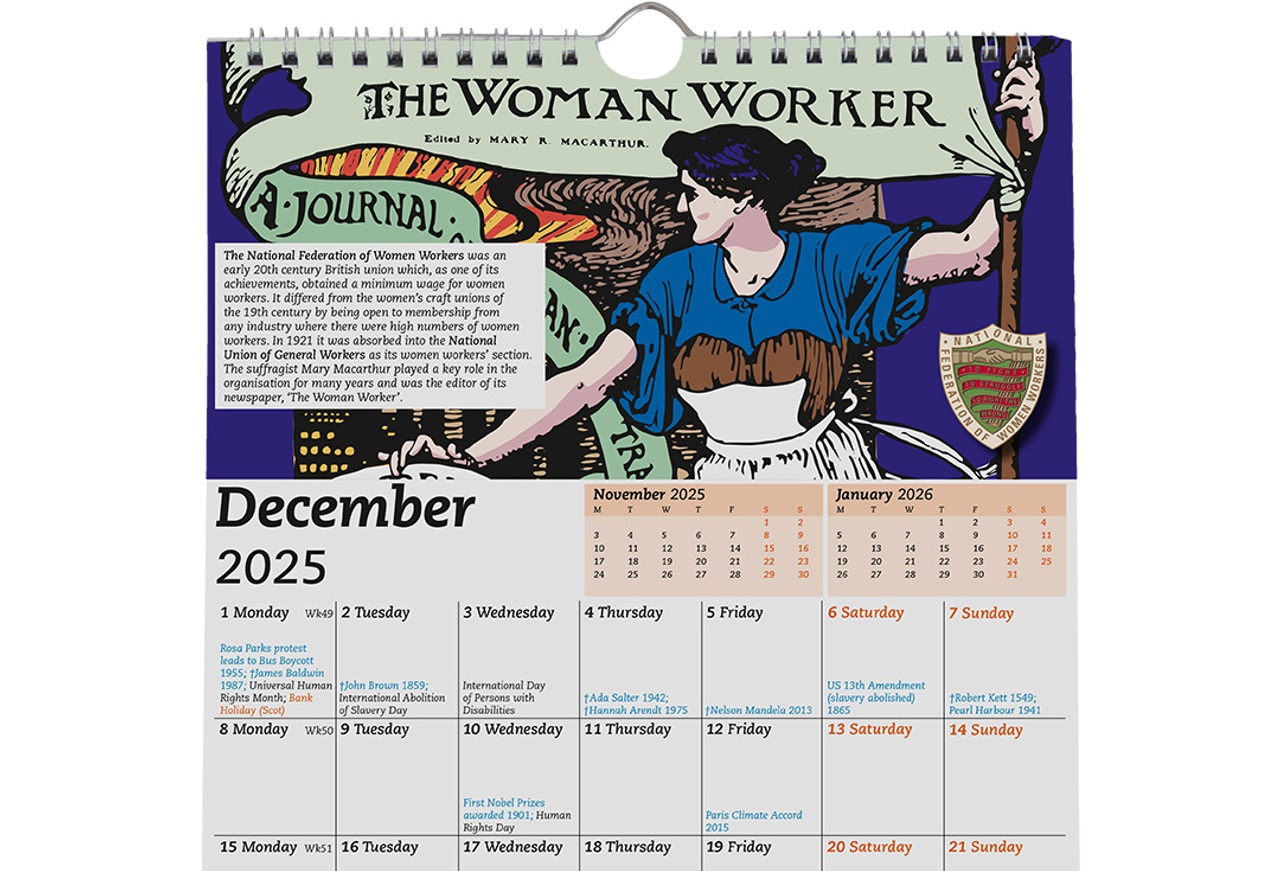

'The Woman Worker' magazine of the NFWW features in December in 2025's Radical Calendar

But it was also due to the absurd political reasoning by male labour leaders that, by excluding women, they could gain political ‘respectability’ on the terms set by the very class they were fighting against.

The exclusion of women from organised labour wasn’t only sexist it was also self-destructive, because women workers formed a large and expanding part of the industrial workforce in Britain.

What’s more, as one of the most precarious and exploited sections of labour, women workers also had more potential for revolutionary action.

Women formed a major source of potential power for working-class struggle in Britain.

The 'Matchgirls' stand against their employer in the 19th century was an important example of industrial action by women

See the Matchgirls' Strike tea towel

Excluded from organising together with men as a united working class by a combo of sexism and political cowardice, women workers began to organise themselves.

Local women’s craft unions were formed, and there were some major industrial actions by women, including the iconic Matchgirls’ Strike of 1888 in London.

But these movements struggled due to their small scale and scattered layout. They lacked the resources and power of a national organisation.

And that’s where the NFWW came in.

In 1906, women labour radicals including the Glaswegian organiser, Mary Macarthur, set up this new trade union to help the women working class to exercise its collective power.

The NFWW jumped right into the struggle. Its first successful strike was for women workers at a box factory in London in 1908.

That was followed by a victory for women chain makers in Cradley Heath, in the Black Country, for whom the NFWW was able to raise a strike fund equivalent to half a million pounds.

In 1913, NFWW organiser Kate McLean helped lead the longest ever women’s strike – five months – to victory among networkers in Ayrshire, Scotland.

Victories brought growth for the NFWW: in 1914, it reached 40,000 members nationally.

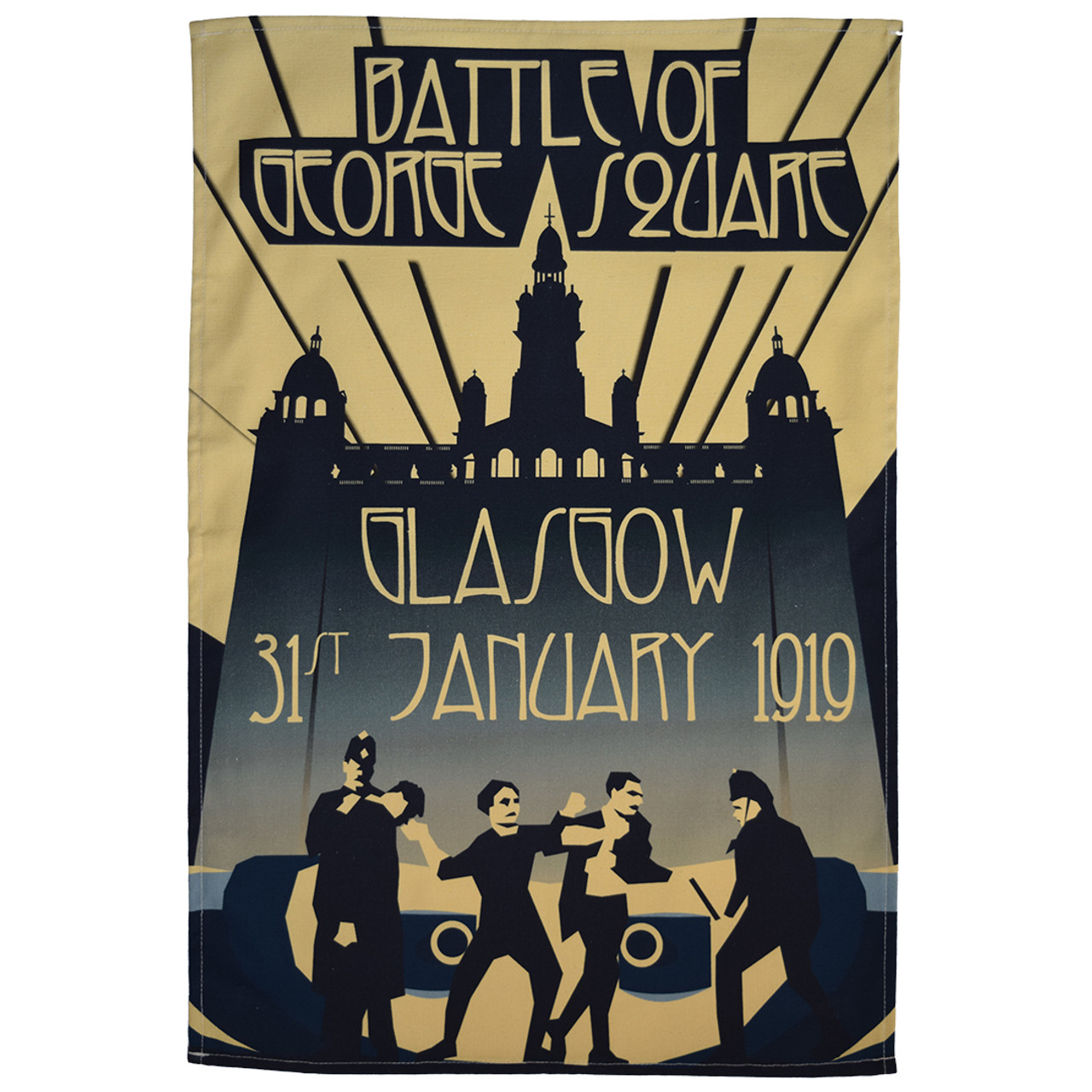

Glasgow, home of trade unionist Mary Macarthur, was an especially active place in the 1910s

See the Battle of George Square tea towel

Then came the First World War, which led to a massive increase of women in the workforce in Britain, with 1 million entering the labour market to replace enlisted and conscripted men between 1914 and 1918.

And whereas school students in Britain know this story quite well, what’s often missed out in textbooks is the fact that the war also saw a major uptick in working-class struggle by women.

In response to declining real wages due to inflation coupled with increased output demands by the government, women workers organised by the NFWW launched a wave of wartime strikes.

At one action in 1916, in a Newcastle munitions factory, the NFWW organised a sit-in strike against the company’s refusal to pay increased wages mandated by a labour relations tribunal.

The strikers spent the sit-in knitting socks for the frontline troops, to demonstrate they were not hostile to the working-class soldiers at the front.

Enraged by the resolve and tactical skill of the strikers, a frothing munitions minister, Winston Churchill, who had shown at Tonypandy in 1910 that he was a sworn enemy of the organised working class in Britain, phoned Mary Macarthur demanding that she end the strike now.

Macarthur calmly informed Churchill that the strike would end when the company conceded the workers’ wage demands – and within just twenty-four hours, it did.

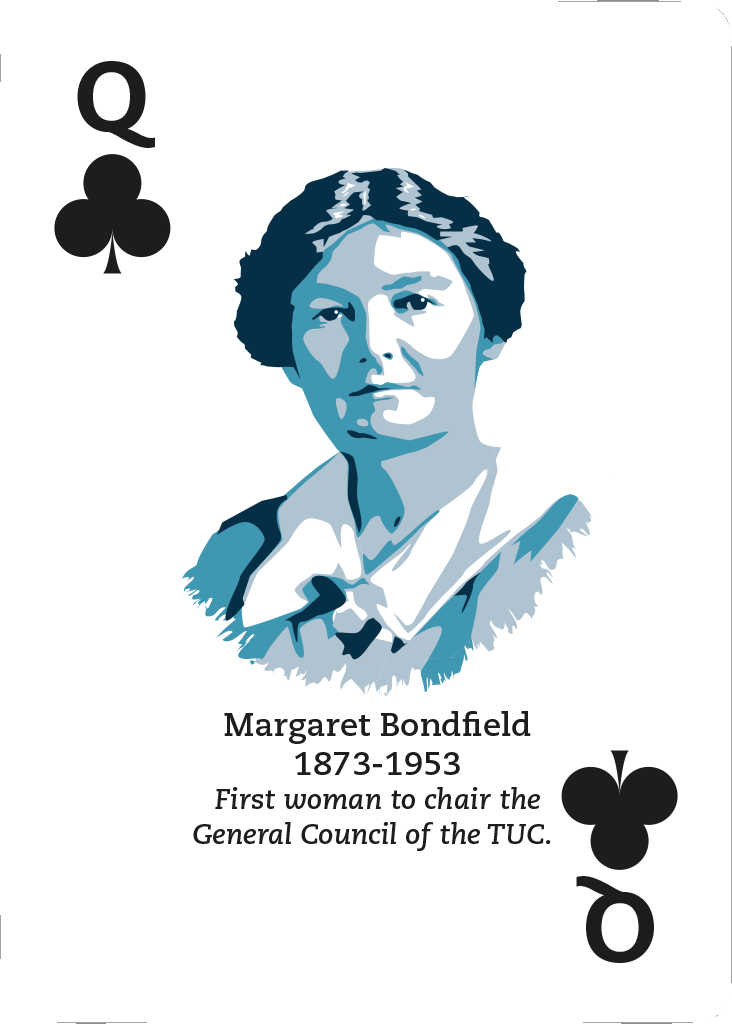

Mary Macarthur was joined at the International Congress of Women Workers by Margaret Bondfield of the TUC

See the International Labour Movement Playing Cards

After the war, the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 created an opportunity for international reorganisation, including for the working class.

Whereas women worker delegates to Paris – in a now familiar experience – were excluded, they were able to link up with their foreign comrades on the margins of the conference.

This led to planning the International Congress of Women Workers (ICWW), which took place this week in 1919.

The ICWW brought together in Washington D. C. women workers from across Europe, the Americas, and Asia.

The NFWW sent Macarthur, and she was joined from Britain by the socialist, Margaret Bondfield, of the TUC.

The Congress had a direct impact on the development of international labour codes created in the post-war years, including a Maternity Protection Convention.

Back home, the NFWW merged with a male union, the National Union of General Workers (NUGW), in 1920, on the assumption that would lead to more class power for women.

In fact, over the 1920s, the women section of the NUGW was marginalised.

But in the longer term, the NFWW had changed the role of women in the labour movement forever.

Ever since, from Ellen Wilkinson to the Grunwick Strike, no one has dared underestimate the power of organised women workers again.