We use cookies to make your shopping experience better. By using our website, you're agreeing to the collection of data as described in our Privacy Policy.

Walking to Freedom: The South African Treason Trial

On this day in 1956, Nelson Mandela and 152 other activists were put on trial in Johannesburg

On 11 February 1990, Nelson Mandela walked free from Victor Verster prison in the Western Cape.

But this wasn’t the first time he’d been released from a South African jail.

In 1961, before Mandela was a global icon, he and several other anti-apartheid activists were released after the ‘not guilty’ verdict in the infamous Treason Trial.

Mandela went on to become South Africa's first black head of state and the first elected in a fully democratic election

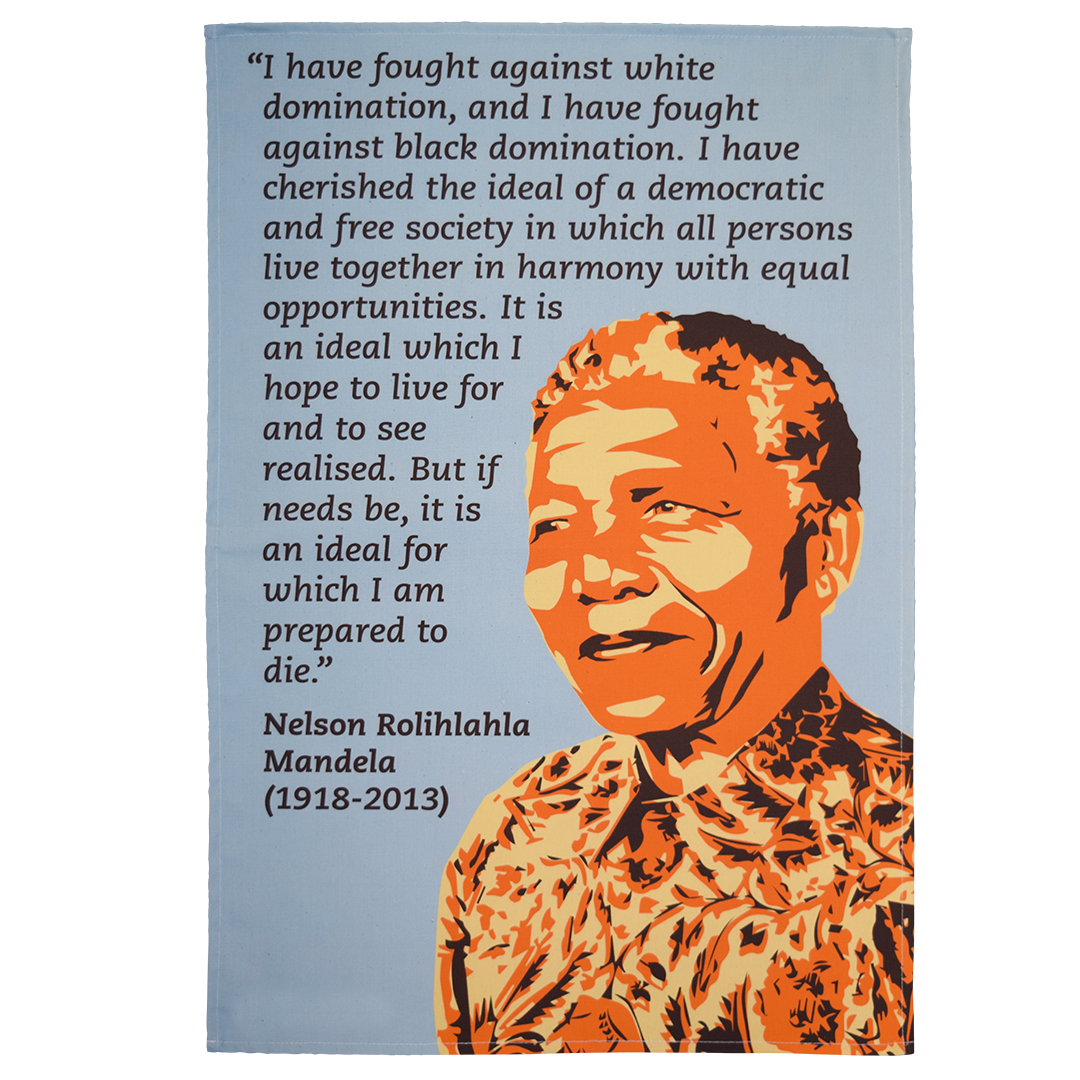

Click to view our Nelson Mandela tea towel

During the 1950s, apartheid South Africa was still trying to gain international acceptance.

The National Party had been elected in 1948, and was busy strengthening the legal apparatus of white supremacy in South Africa.

The existence of this regime, based upon a white minority, was dependent upon support from the West.

But with Europe still reeling from the war against Nazism and its

racist ideology, Western powers were understandably hesitant to befriend an apartheid state like South Africa.

At the same time, though, an even larger threat loomed in the Western consciousness: the threat of communism.

The Cold War had begun, and the West seemed ready to sacrifice everything to anti-communism. That’s how

Francisco Franco's fascist government in Spain re-entered polite society.

As they say, the enemies of your enemies are your friends: and the white supremacists in South Africa made sure to sell themselves as reliable anti-communists.

Franco's Spain used anti-communist sentiment to rehabilitate its international image

Click to view our Help Spain tea towel

In 1950, the South African government passed the Suppression of Communism Act.

The South African Communist Party (SACP) and other communist groups did form a key element in the anti-apartheid coalition. However, as with

McCarthyism in the U.S., the brush of anti-communism was used to attack a much broader swathe of left-wing politics.

The National Party government wanted to use the Act to destroy the African National Congress (ANC), whose membership, for the most part, were not communist.

As part of the crackdown, on 5 December 1956, over 150 activists were arrested in police raids.

Most of the key figures in the anti-apartheid movement were picked up: Mandela,

Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Ruth First, and Joe Slovo.

They were to be tried for treason, on very dubious grounds, under the Suppression of Communism Act.

The move drew international condemnation by progressive groups. The U.K. Labour Party called it the action of a police state.

Mandela went on to become a vocal activist for justice across the world, from Palestine to Iraq

Click to view our Palestine tea towel

As it turned out, though, the trial was a shambles for the South African regime.

It was besieged by protestors from the outset, singing the African protest anthem “Nkosi Sikeleli Afrika” – “Lord Bless Africa” – outside the court room.

And the trial itself dragged on for

five years, with the prosecution regularly unsure of what supposed activities it was focusing on. The attempt to equate the ANC with communism was becoming an embarrassing failure.

Over the course of the trial, over one hundred of the defendants had to be set free as the state gave up on being able to convict them.

By the end, only 30 of the original defendants remained – and even these were found not guilty by the trial judge.

On one level, the verdict probably had a propaganda objective, to pretend that South Africa enjoyed impartial justice. But it was also a genuine defeat for the Apartheid regime.

There was still a very long way to go, though. Apartheid had only gotten more violent during the Treason Trial, with the Sharpeville Massacre perpetrated in 1960.

And Mandela, with other Treason Trial defendants, was sentenced to life imprisonment just three years later, at the Rivonia Trial of 1963-64.

But the experience of the Treason Trial had helped equip the anti-apartheid movement for the struggle ahead.

It was during the trial that the international anti-apartheid movement really took off. In the U.K.,

Canon John Collins of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament set up the Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa, which contributed £75,000 to the defendants’ legal costs.

Meanwhile, the numerous defendants used their imprisonment during the trial to deepen and expand activist networks inside South Africa.

On this basis, the struggle to overthrow apartheid in South Africa would eventually prevail. The long walk to freedom had begun.